Unveiling Oahu’s Vulnerability: The 1925 Army-Navy War Game and Its Lasting Lessons

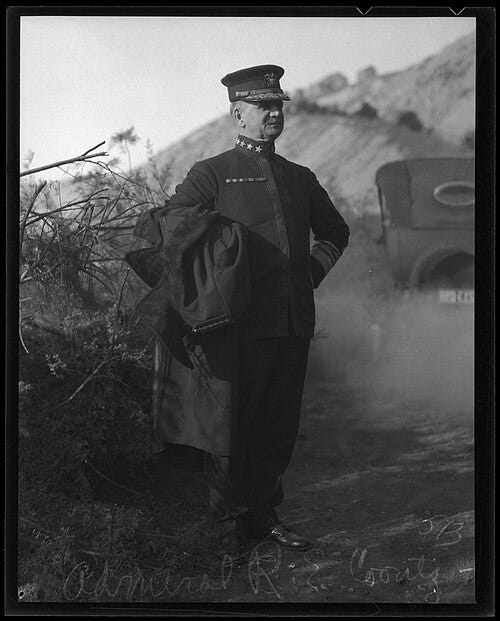

In April 1925, the United States military conducted a pivotal war game in Hawaii, pitting the defending Black forces against the attacking Blue fleet to test the defenses of Oahu, a critical Pacific stronghold. Led by Major General John L. Hines, Chief of Staff of the Army, and Admiral Robert E. Coontz, of the Great White Fleet fame, the exercise exposed significant weaknesses in Oahu’s garrison, particularly its inadequate troop numbers and lack of mobile reserves. Published by the Associated Press and reprinted in newspapers like the Evening Star on June 7, 1925, Hines’ candid assessment underscored the need for enhanced fortifications, a lesson that resonated tragically sixteen years later during the attack on Pearl Harbor. This historic article not only details the strategic insights gained from the maneuvers but also serves as a sobering reminder of the importance of military preparedness in an increasingly volatile world. Below is the full transcript of the Evening Star article, preserving the original text and its insights into a critical moment in U.S. military history.1

GEN. HINES CLAIMS HAWAIIAN GARRISON INADEQUATE IN WAR

Troops and Aircraft Force Insufficient to Defend Islands, He Declares.

By the Associated Press

Defense of the Hawaiian Islands must be intrusted to an adequate mobile force—troops and aircraft—and the recent grand joint Army and Navy maneuvers to test that theory demonstrated that the present garrison is inadequate in both respects in the judgment of Maj. Gen. John L. Hines, chief of staff and one of the chief umpires in the great war game.

“A commander (of the Hawaiian garrison) must not only have enough troops to hold the essential positions and to man his armament, but he must have enough troops left to form an adequate reserve,” Gen. Hines said in the first official explanation of the joint maneuvers and their results to be given out. “In this instance, the commander could not do this, for his force was not adequate for the task assigned to it. He did all that he could with the forces given him; he could not do the impossible.”

In describing the operations and strategic problem the commander on each side had to face, Gen. Hines pointed out that it would be difficult to say what would have been the fate of either landing operation on the Island of Oahu in actual war.

“Considering the two cases on their merits, I am of the opinion that the landing on the west coast would probably have failed in war, but that the landing on the north coast might well have succeeded,” he said. “There is no doubt that highly trained, well led infantry can establish a beachhead once the troops are ashore. The critical period of a landing operation is that in which the landing troops are moving in boats from transports to beach.”

Objects of Maneuvers.

Outlining the objects of the test maneuvers and the plans of offense and defense followed by the opposing commanders, Gen. Hines said:

“The grand joint exercise just concluded in Hawaii was the biggest and most interesting one ever held by our Army and Navy. It had two principal objects:

“1. To test the project and plans for the defense of Oahu, and

“2. To train Army and Navy in joint operations.

“The following facts were assumed:

“1. That a state of war existed between Blue (the United States) and Black:

“2. That the Hawaiian Islands were a Black possession and were defended by the existing armament, the present naval district forces and a garrison of approximately 14,000 men; and

“3. That Blue was desirous of capturing Oahu, with the object of making use of it as a naval base.

“The Blue fleet, accompanied by an expeditionary force of two divisions of troops, was concentrated in San Francisco and put to sea April 15. Under the terms of the problem the transports accompanying the fleet were not to be farther than 1,700 miles from San Francisco at 5 a.m., April 25, 1925, the hour and date when the problem actually opened. The Black or Hawaiian side was restricted to the use of forces and means actually available, whereas the Blue fleet had two constructive divisions of troops, represented by some 1,500 marines.

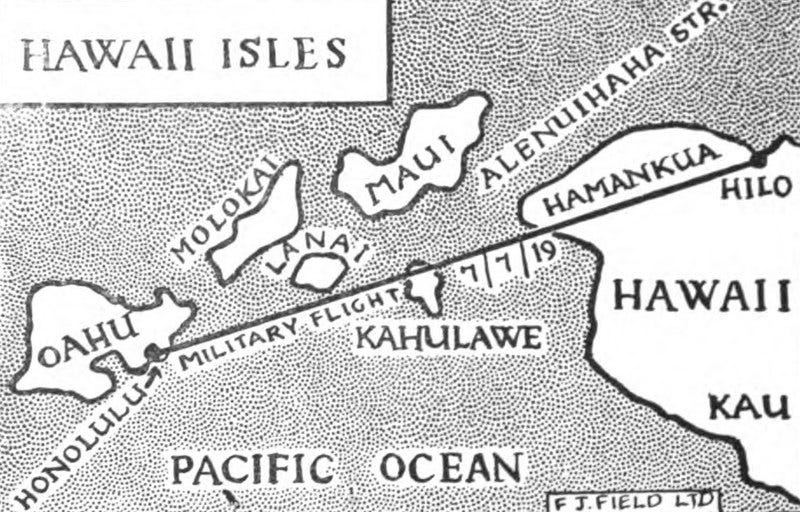

Black knew of the impending attack in ample time and estimated that Blue would seize a base on Lanai, one of the islands of the group, preparatory to launching an attack against Oahu itself. Black was in a difficult situation. No reinforcements could be expected, and neither air forces, subsurface nor fast surface vessels were available in sufficient strength to permit Black to deny any of the outlying islands to Blue.

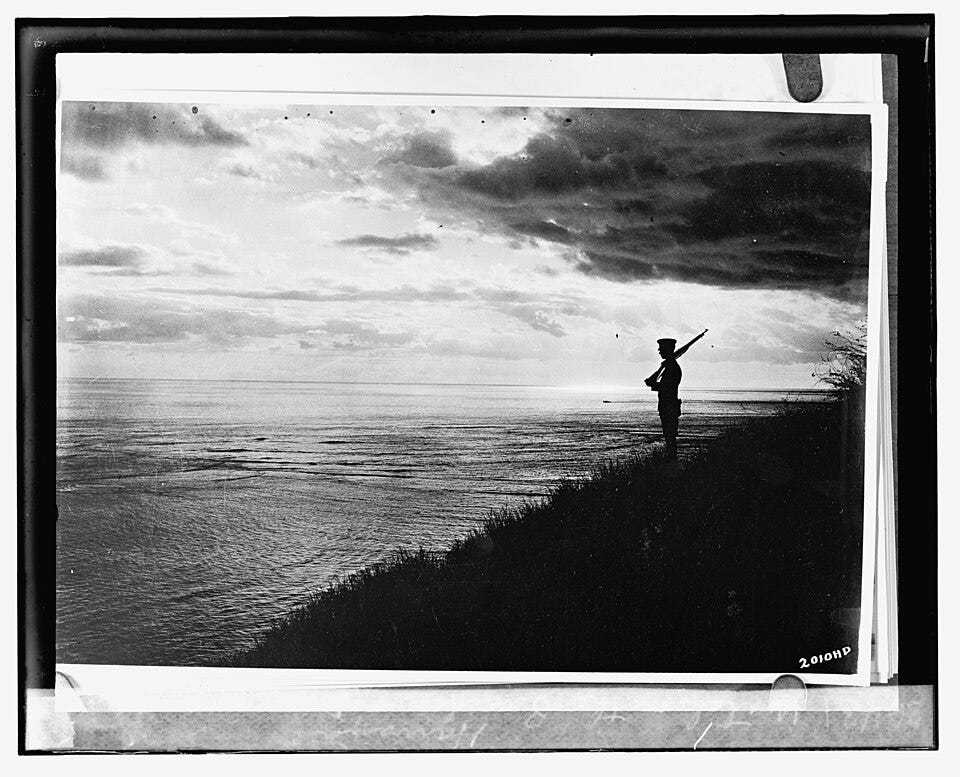

“The arrangements made for defense were, in general, admirable and were efficiently carried out, the conduct of practically all forces engaged being exemplary. Every one was on the qui vive.2 Possible landing places were held by a thin beach cordon, plentifully supplied with field guns, machine guns, etc., and backed by strong points and small mobile reserves. The Black air forces, both Army and Navy, were concentrated on Oahu, seven DH4B’s being, however, dispatched to the Island of Lanai. The surface and subsurface vessels and aircraft of the naval district formed an observation cordon around Oahu at a sufficient distance to give timely warning of the enemy’s approach.

“Blue’s task was also difficult, in that it involved an attack against a strongly fortified island some 2,000 miles from Blue’s nearest home base. In the very nature of the case such an attack was a major operation and therefore required extensive and careful preparations. Since a direct attack against Oahu was too hazardous, Blue planned to seize one of the outlying air base there and to follow this with a naval demonstration against a bay on the south coast of Oahu for the purpose of diverting Black’s attention. Blue then proposed to direct his main landing attack against the north coast of Oahu, while simultaneously therewith making a secondary landing on the west coast of Oahu.

“Blue was successful, not only in seizing Molokai but Lanai as well, and in occupying the landing fields of both islands early on the 25h. This success may be ascribed in large measure to the fact that, instead of moving the airplane carrier Langley close inshore and exposing her to attack by Black submarines, Blue kept her well offshore and had her fly her planes off to the landing fields on Molokai and Lanai as soon as these had been seized by the advance force. The seven Black airplanes dispatched to Lanai gave a good account of themselves, sinking a Blue tender and inflicting serious damage on the Blue landing force. They were far too weak to prevent the seizures of the two islands.

Attack Anticipated.

“Blue anticipated that the main hostile attack would be launched against the west coast. With the forces at his disposal it was physically impossible for the Black commander to have adequate local reserves on both west and north coasts, and to hold out general reserves.

“Confronting two attacks, one on the west coast and one on the north, he felt compelled to estimate one as the main attack and the other as secondary. The immediate consequences of a successful attack on the west coast were more serious than on the north coast. Therefore, Black placed the bulk of his forces so as to meet this attack. With adequate general reserves to meet any action of Blue, this risk would not have had to be taken. As it turned out the bulk of the forces were too far from the north coast of Oahu to repulse the major debarkation promptly.

“Blue had been successful in seizing a base in dangerous proximity to Oahu. With local command of the sea and with a superior air force in his hands, Blue was reasonably sure of ultimate victory. But Black aircraft and submarines did all in their power to make winning as hard and costly as possible to Blue.

“Blue’s first move against Oahu consisted of a naval demonstration on the evening of April 26. This was designed as a feint, but did not have any practical result, for it did not deceive Black for a moment and merely served to bring Blue ships under the fire of heavy Black batteries. Blue then launched his main attack against the north (or open) coast of Oahu at daylight on the 27th, landing troops under cover of and supported by heavy fire from his ships. The weather was ideal and there was practically no surf. The landing was vigorously opposed, but the defense forces finally had to retire. Simultaneously with this main attack, Blue made a secondary landing on the west coast under cover of and supported by heavy fire from his ships. Here considerable surf was encountered and the landing failed in face of the vigorous defense. It is to be noted that both landings were planned to begin at 1:30 a.m., April 27, but orders were issued that they were actually to begin four hours later so as to obviate the inevitable hazards of life and material involved in making landings at night.

Landing Would Have Succeeded.

“It is, of course, extremely difficult to say whether either landing would have succeeded in an actual case. The local umpires on the spot were of the opinion that the landing on the north coast succeeded, Blue suffering severe losses, and that the landing on the west coast failed. Considering the two cases on their merits, I am of the opinion that the landing on the west coast would probably have failed in war, but that the landing on the north coast might well have succeeded. There is no doubt that highly trained, well led infantry can establish a beachhead once the troops are ashore. Even when the landings, as in the exercise, are well planned and covered by naval gun fire, the guns defending the beach will sink many boats, perhaps even transports. Even under the best weather conditions the critical period of a landing operation is that in which the landing troops are moving in boats from transports to beach. During this period they are exposed helpless to the gun, machine gun and rifle fire of the defender, and, in case he has any aircraft left, to attacks by the latter.

“But these landing operations demonstrate another lesson. The defense against them must be flexible and mobile. Dependence must not be placed primarily or even predominantly upon mechanical means—field guns and machine guns—but upon mobile troops and aircraft, counter-attacking whenever and wherever necessary. A commander must not only have troops enough to hold the essential positions and to man his armament, but he must have enough troops left to form an adequate reserve.

“ In this instance, the commander could not do this, for his force was not adequate for the task assigned to it. He did all he could with the forces given him; he could not do the impossible.

“Analyzing the results of the exercises from the standpoint of their objects, it is believed—

“1. That the project and plans for the defense of Oahu have been tested and that the deficiencies therein have been disclosed.

“2. That very valuable training has been given the Army and the Navy in joint operation.

“These results fully justify the time and effort spent in the exercises.”

“Gen. Hines Claims Hawaiian Garrison Inadequate in War,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), June 7, 1925, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1925-06-07/ed-1/seq-1/.

Qui vive - alert, lookout, carefully keeping watch; a sentry’s challenge.