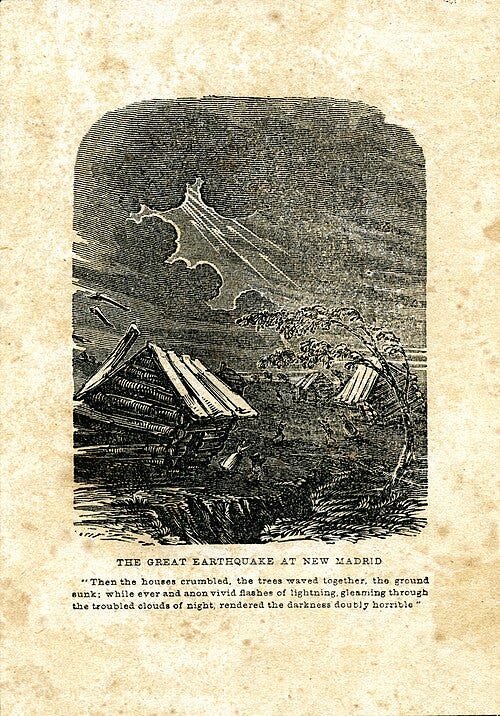

Tremors of Terror: Eyewitness Accounts of the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811-1812

The New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811-1812 stand as one of the most significant seismic events in North American history, shaking the Mississippi River Valley with unparalleled intensity. Centered in what is now southeast Missouri, northeast Arkansas, and western Tennessee, these quakes, occurring primarily between December 1811 and February 1812, left a profound impact on the sparsely populated frontier. With magnitudes estimated between 7.0 and 8.0, the earthquakes reshaped the landscape, altered river courses, and instilled widespread fear among settlers and Indigenous communities alike. The following primary source materials, drawn from John B. Bradbury’s Travels in the Interior of America (1819), Colonel John Shaw’s personal narrative (1855), and an article from the Alexandria Daily Gazette (1812), offer vivid firsthand accounts of the chaos, terror, and human resilience in the face of nature’s fury. These narratives capture not only the physical destruction but also the psychological and cultural reverberations, including the spiritual responses of Indigenous tribes. Through these accounts, we glimpse a world convulsed by natural disaster, where survival demanded quick thinking and communal solidarity.123

John B. Bradbury, Travels in the Interior of America, in the Years 1809, 1810, and 1811

In the evening we came in view of a dangerous part of the river, called by the Americans the Devil's Channel, and by the French Chenal du Diable. It appears to be caused by a bank that crosses the river in this place, which renders it shallow. On this bank, a great number of trees have lodged; and, on account of the shallowness of the river, a considerable portion of the branches are raised above the surface; through these the water rushes with such impetuosity as to be heard at the distance of some miles.

As it would require every effort of skill and exertion to pass through this channel in safety, and as the sun had set, I resolved to wait until the morning, and caused the boat to be moored to a small island, about five hundred yards above the entrance into the channel. After supper we went to sleep as usual; and in the night, about ten o'clock, I was awakened by a most tremendous noise, accompanied by so violent an agitation of the boat that it appealed in danger of upsetting. Before I could quit the bed, or rather the skin, upon which I lay, the four men who slept in the other cabin rushed in, and cried out in the greatest terror, “O mon Dieu! Monsieur Bradbury, qu’est ce qu'il y a?” [Oh my God! Mr. Bradbury, what is it?] I passed them with some difficulty, and ran to the door of the cabin, where I could distinctly see the river agitated as if by a storm; and although the noise was inconceivably loud and terrific, I could distinctly hear the crash of falling trees, and the screaming of the wild fowl on the river, but found that the boat was still safe at her moorings. I was followed by the men and the patron, who, in accents of terror, were still enquiring what it was: I tried to calm them by saying, “Restez vous tranquil, c'est un tremblement de terre,” [Stay calm, it’s an earthquake.] which term thet did not seem to understand.

By the time we could get to our fire, which was on a large flag, in the stern of the boat, the shock had ceased; but immediately the perpendicular banks, both above and below us, began to fall into the river in such vast masses, as nearly to sink our boat by the swell they occasioned; and our patron, who seemed more terrified even than the men, began to cry out, “O mon Dieu! nous perirons!” I wished to consult with him as to what we could do to preserve ourselves and the boat, but could get no answer except “O mon Dieu! nous perirons!" [Oh my God! We will perish!] and “Allons d terre! Allans d terre!” [Let’s go ashore! Let’s go ashore!] As I found Mr. Bridge the only one who seemed to retain any presence of mind, we consulted together, and agreed to send two of the men with a candle up the bank, in order to examine if it had separated from the island, a circumstance that we suspected, from hearing the snapping of the limbs of some drift trees, which were deposited between the margin of the river and the summit of the bank. The men, on arriving at the edge of the river, cried out, “Venez d terre! Venez d terre!” [Come ashore! Come ashore!] and told us there was a fire, and desired Mr. Bridge and the patron to follow them; and as it now occurred to me that the preservation of the boat in a great measure depended on the depth of the river, I tried with a sounding pole, and to my great joy, found it did not exceed eight or ten feet.

Immediately after the shock we observed the time, and found it was near two o'clock. At about nearly half-past two, I resolved to go ashore myself, but whilst I was securing some papers and money, by taking them out of my trunks, another shock came on, terrible indeed, but not equal to the first. Morin, our patron, called out from the island, “Monsieur Bradbury! sauvez vous, sauvez vous!” [Mr. Bradbury! Save yourself, save yourself!] I went ashore, and found the chasm really frightful, being not less than four feet in width, and the bank had sunk at least two feet. I took the candle to examine its length, and concluded that it could not be less than eighty yards; and at each end, the banks had fallen into the river. I now saw clearly that our lives had been saved by our boat being moored to a sloping bank. Before we completed our fire, we had two more shocks, and others occurred during the whole night, at intervals of from six to ten minutes, but they were slight in comparison with the first and second. At four o'clock I took a candle, and again examined the bank, and perceived to my great satisfaction that no material alteration had taken place; I also found the boat safe, and secured my pocket compass. I had already noticed that the sound which was heard at the time of every shock, always preceded it at least a second, and that it uniformly came from the same point, and went off in an opposite direction. I now found that the shock came from a little northward of east, and proceeded to the westward. At day-light we had counted twenty-seven shocks during our stay on the island, but still found the chasm so that it might be passed. The river was covered with foam and drift timber, and had risen considerably, but our boat was safe. Whilst we were waiting till the light became sufficient for us to embark, two canoes floated down the river, in one of which we saw some Indian corn and some clothes. We considered this as a melancholy proof that some of the boats we passed the preceding day had perished. Our conjectures were afterwards confirmed, as we learned that three had been overwhelmed, and that all on board had perished. When the daylight appeared to be sufficient for us, I gave orders to embark, and we all went on board. Two men were in the act of loosening the fastenings, when a shock occurred nearly equal to the first in violence. The men ran up the bank, to save themselves on the island, but before they could get over the chasm, a tree fell close by them and stopped their progress. As the bank appeared to me to be moving rapidly into the river, I called out to the men in the boat, “Coupez les cordes!” [Cut the ropes!] on hearing which, the two men ran down the bank, loosed the cords, and jumped into the boat. We were again on the river: the Chenal da Diable was in sight, but it appeared absolutely impassable, from the quantity of trees and drift wood that had lodged during the night against the planters fixed in the bottom of the river ; and in addition to our difficulties, the patron and the men appeared to be so terrified and confused, as to be almost incapable of action. Previous to passing the channel, I stopped that the men might have time to become more composed. I had the good fortune to discover a bank, rising with a gentle slope, where we again moored, and prepared to breakfast on the island. Whilst that was preparing, I walked out in company with Morin, our patron, to view the channel, to ascertain the safest part, which we soon agreed upon. Whilst we were thus employed, we experienced a very severe shock, and found some difficulty in preserving ourselves from being thrown down; another occurred during the time we were at breakfast, and a third as we were preparing to re-embark. In the last, Mr. Bridge, who was standing within the declivity of the bank, narrowly escaped being thrown into the river, as the sand continued to give way under his feet. Observing that the men were still very much under the influence of terror, I desired Morin to give to each of them a glass of spirits, and reminding them that their safety depended on their exertions, we pushed out into the river. The danger we had now to encounter was of a nature which they understood: the nearer we approached it, the more confidence they appeared to gain; and indeed, all their strength, and all the skill of Morin, was necessary; for for there being no direct channel through the trees, we were several times under the necessity of changing our course in the space of a few seconds, and that so instantaneously, as not to leave a moment for deliberation. Immediately after we had cleared all danger, the men dropped their oars, crossed themselves, then gave a shout, which was followed by mutual congratulations on their safety.

We continued on the river till eleven o'clock, when there was another violent shock, which seemed to affect us as sensibly as if we had been on land. The trees on both sides of the river were most violently agitated, and the banks in several places fell in, within our view, carrying with them innumerable trees, the crash of which falling into the river, mixed with the terrible sound attending the shock, and the screaming of the geese and other wild fowl, produced an idea that all nature was in a state of dissolution. During the shock, the river had been much agitated, and the men became anxious to go ashore: my opinion was, that we were much safer on the river; but finding that they laid down their oars, and that they seemed determined to quit the boat for the present, we looked out for a part of the river where we might moor in security, and having found one, we stopped during the remainder of the day.

At three o'clock, another canoe passed us adrift on the river. We did not experience any more shocks until the morning of the 17th, when two occurred; one about five and the other about seven o'clock. We continued our voyage, and about twelve this day, had a severe shock, of very long duration. About four o'clock we came in sight of a log-house, a little above the Lower Chickasaw bluffs. More than twenty people came out as soon as they discovered us, and when within hearing, earnestly entreated us to come ashore. I found them almost distracted with fear, and that they were composed of several families, who had collected to pray together. On entering the house. I saw a bible lying open on the table. They informed me that the greatest part of the inhabitants in the neighbourhood had fled to the hills, on the opposite side of the river, for safety; and that during the shock, about sun-rise on the l6th, a chasm had opened on the sand bar opposite the bluffs below, and on closing again, had thrown the water to the height of a tall tree. They also affirmed that the earth opened in several places back from the river. One of the men, who appeared to be considered as possessing more knowledge than the rest, entered into an explanation of the cause, and attributed it to the comet that had appeared a few months before, which he described as having two horns, over one of which the earth had rolled, and was now lodged betwixt them: that the shocks were occasioned by the attempts made by the earth to surmount the other horn. If this should be accomplished, all would be well, if otherwise, inevitable destruction to the world would follow. Finding him confident in his hypothesis, and myself unable to refute it, I did not dispute the point, and we went on about a mile further. Only one shock occurred this night, at half past seven o'clock. On the morning of the 18th, we had two shocks, one betwixt three and four o'clock, and the other at six. At noon, there was a violent one of very long duration, which threw a great number of trees into the river within our view, and in the evening, two slight shocks more, one at six, the other at nine o’clock.

19th. — We arrived at the mouth of the river St. Francis, and had only one shock, which happened at eleven at night.

20th.— Detained by fog, and experienced only two shocks, one at five, the other at seven in the evening.

21st. — Awakened by a shock at half past four o'clock: this was the last, it was not very violent, but it lasted for nearly a minute.

On the 24th in the evening, we saw a smoke, and knowing that there were no habitations on this part of the river, we made towards it, and found it to be the camp of a few Choctaw Indians, from whom I purchased a swan, for five balls and five loads of powder.

25th. — Monsieur Longpre overtook us, and we encamped together in the evening. He was about two hundred miles from us on the night of the 15th, by the course of the river, where the earthquakes had also been very terrible. It appeared from his account, that at New Madrid the shock had been extremely violent: the greatest part of the houses had been rendered uninhabitable, although, being constructed of timber, and framed together, they were better calculated to withstand the shocks than buildings of brick or stone. The greatest part of the plain on which the town was situated was become a lake, and the houses were deserted.

New Madrid Earthquake.

Account of Col. John Shaw.

The “Personal Narrative of Col. John Shaw, of Marquette county, Wisconsin,” contained in the second annual report and collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, for the year 1855, gives an account of the New Madrid earthquake of 1811 and 1812.

As might be expected the accounts of the earthquake by persons who were in that region of country at the time are not numerous, and as this statement of Col. Shaw’s is not accessible to many, it is here reprinted:

“While lodging about thirty miles north of New Madrid, on the 14th of December, 1811, about 2 o’clock in the morning, occurred a heavy shock of an earthquake. The house, where I was stopping, was partly of wood and partly of brick structure; the brick portion all fell, but I and the family all fortunately escaped unhurt. At the still greater shock, about 2 o’clock in the morning of the 7th of February, 1812, I was in New Madrid, when nearly two thousand people of all ages, fled in terror from their falling dwellings, in that place and the surrounding country, and directed their course north about thirty miles to Tywappety Hill, on the western bank of the Mississippi, and about seven miles back from the river. This was the first high ground above New Madrid, and here the fugitives formed an encampment. It was proposed that all should kneel, and engage in supplicating God’s mercy, and all simultaneously, Catholics and Protestants, knelt and offered solemn prayer to their Creator.

About twelve miles back towards New Madrid, a young woman about seventeen years of age, named Betsey Masters, had been left by her parents and family, her leg having been broken below the knee by the falling of one of the weight-poles of the roof of the cabin; and, though a total stranger, I was the only person who would consent to return and see whether she still survived. Receiving a description of the locality of the place, I started, and found the poor girl upon a bed, as she had been left, with some water and corn bread within her reach. I cooked up some food for her, and made her condition as comfortable as circumstances would allow, and returned the same day to the grand encampment. Miss Masters eventually recovered.

In abandoning their homes, on this emergency, the people only stopped long enough to get their team, and hurry in their families and some provisions. It was a matter of doubt among them, whether water or fire would be most likely to burst forth, and cover all the country. The timber land around New Madrid sunk five or six feet, so that the lakes and lagoons, which seemed to have their beds pushed up, discharged their waters over the sunken lands. Through the fissures caused by the earthquake, were forced up vast quantities of a hard, jet black substance, which appeared very smooth, as though worn by friction. It seemed a very different substance from either anthracite or bituminous coal.

This hegira, with all its attendant appalling circumstances, was a most heart-rending scene, and had the effect to constrain the most wicked and profane, earnestly to plead to God in prayer for mercy. In less than three months, most of these people returned to their homes, and though the earthquakes continued occasionally with less destructive effects, they became so accustomed to the recurring vibrations, that they paid little or no regard to them, not even interrupting or checking their dances, frolics and vices.

Excerpt from the following article written in the Alexandria daily gazette, commercial & political, April 17, 1812:

St. Louis, (U.L.) March 21.

Indian Murders, &c.

The Cherokees, who were exploring that tract of country between the Arkansas and White river, have returned home, terrified by the repeated & violent shocks of earthquakes. We understand they intended to exchange with the United States, their country on the east of Mississippi, for a like quantity on the Arkansas.

The tremendous effects of Earthquake in this territory has revived, an almost obsolete Indian rite, in the mode of imploring the Deity, and to avert the Divine displeasure—Temples are erecting in the Indian villages, to make offerings to the Great Spirit. The Shawanees (Sic) of the Maramec (Sic), [40 miles from this place] have finished their religious devotions. The following authentic account of it may be interesting to our readers.

The Indian mode of worship, as happened in consequence of the late earthquake.

This alarming phenomenon of nature struck with such consternation and dismay those tribes of Indians that live within and contiguous to that tract of country, on the Mississippi where the severity of the earthquake appears to have been greatest, that they were induced to convene together in order to consult upon the necessity of having recourse to some method of relief from so alarming an incident; when it was resolved to fall upon the following expedient to excite the pity of the Great Spirit.

After a general hunt had taken place to kill deer enough for the undertaking, a small hut was built to represent a temple, or place of offering sacrifice.

The ceremony was introduced by a general cleansing of the body and face. The novelty of the occasion rendering it unusually awful & interesting. After neatly skinning their deer, they suspend them by the fore feet, so that their heads might be directed to the heavens, before the temple, as an offering to the Great Spirit. In this attitude they remained for three days; which interval was devoted to such penance, as consists in absolute fastings; at night laying upon the back upon fresh deer skins; turning their thoughts exclusively upon the happy prospects of immediate protection; that they may conceive dreams to that effect the only vehicle of intercourse between them and the Great Spirit; the old and young men observing a most rigorous abstinence from a co-habitation with the women, under the solemn persuasion that, for a failure thereof, instant death and condemnation awaited; and lastly, gravely and with much apparent piety, imploring the attention of the Great Spirit to their helpless and distressed condition; acknowledging their absolute dependence on him; entreating his regard to their wives and children; declaring the fatal consequences that must inevitably ensure by withholding his notice; namely, the loss of their wives and children; and their total disability to master their game, arising from their constant dread of his anger, and concluded in asserting their full assurance that their prayers are heard, their object is accomplished by a cessation of terrors, and game becoming again plenty and easily overcome.

On the lapse of the three days, thus dedicated, believing themselves forgiven for every unwarrantable act of which they were sensible, that the offering was accepted; they finally begin with a mutual relation of their respective dreams; the scene is changed to joy and congratulation, by proceeding ravenously to devour the sacrificed deer to allay their fast.

We are informed from a respectable source that the old road to the post of Arkansas, by Spring river, is entirely destroyed, by the last violent shocks of earthquake; chasms of great depth and considerable length cross the country in various directions, some swamps have become dry, other deep lakes, in some places hills have disappeared.

John B. Bradbury, Travels in the Interior of America, in the Years 1809, 1810, and 1811: Including a Description of Upper Louisiana, Together With the States of Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, and Tennessee, With the Illinois and Western Territories: and Containing Remarks and Observations Useful to Persons Emigrating to Those Countries, (London: Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, 1819), 207-216.

John Shaw, “Personal Narrative of Col. John Shaw,” in Second Annual Report and Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, for the Year 1855, (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1856), accessed via https://www.memphis.edu/ceri/compendium/pdfs/shaw.pdf.

“Indian Murders, &c.,” Alexandria Daily Gazette, Commercial & Political, April 17, 1812, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024013/1812-04-17/ed-1/seq-2/.