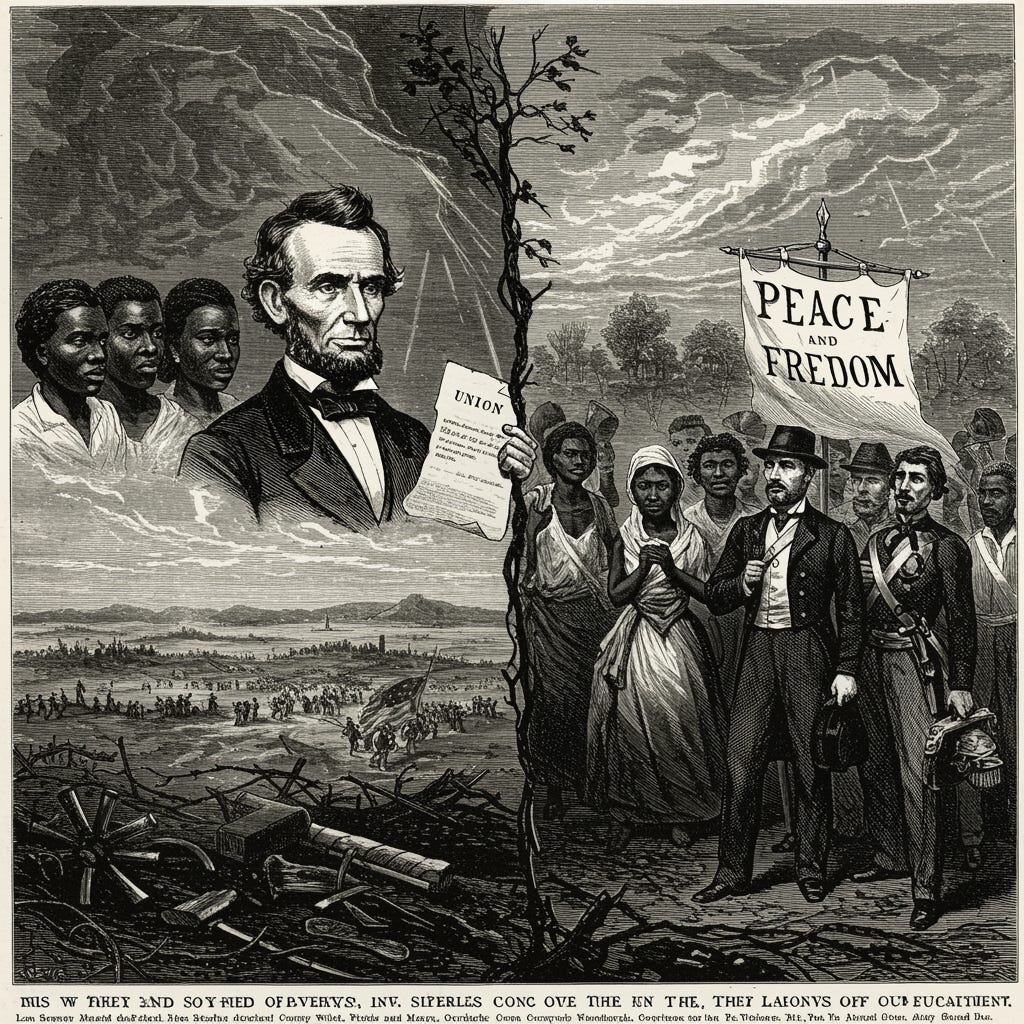

Modern American students often learn that the Civil War was fought primarily to end slavery, driven by a moral commitment to natural rights. However, this narrative oversimplifies the complex motives of the era, as voiced by 19th-century abolitionists. In the article "The War in America," published in The Liberator on November 28, 1862, abolitionists articulate a starkly different perspective. They argue that the war was not waged for emancipation but for Union and empire, revealing President Lincoln’s pragmatic approach to slavery as a tool for preserving the nation. Some abolitionists even opposed the war itself, adhering to nonviolent principles or doubting its ability to secure true freedom for enslaved people. Moreover, they foresaw Northern resistance to freed slaves’ migration, exposing the era’s deep racial prejudices. This article challenges the victor’s narrative that has shaped historical memory, offering a critical lens on the Civil War’s true objectives and the marginalized voices of abolitionists. Below is a full transcript of this historic piece, republished from The Liberator.1

THE WAR IN AMERICA.

It is really singular to observe how few persons have the courage to adhere consistently to a principle through evil report and good report, or who can even intelligently and generously appreciate the conduct of those who do. We are, for instance, pledged to the doctrine that all war is unchristian and unlawful; and yet there had been no war waged in our time but we have had some good people, who, without calling in question the theoretical soundness of our principle, have passionately pleaded that we should virtually waive it in favor of that particular war. It was not the same class of persons, of course, that favored all these wars, but there were some who espoused the cause of each, and maintained that it ought to be treated as exceptional to our general rule; so that if we had followed the counsel of these well-meaning friends, we should have been in this position: that, while condemning all war in the abstract, we should have been defending each war in the concrete. But with all respect to our worthy advisers, we cannot thus accommodate our principle to their individual predilections, and we can all the less do it, because we believe that, in almost every case, events have proved, after the war was over, that the course we have pursued as a matter of principle was the right one also as a matter of policy.

As usual, there are some who maintain that we are wrong in opposing the civil war in America, because it is a war in favor of freedom. We will endeavor to explain once more to these friends why it is that we cannot join in anything that shall tend to encourage and protract this most appalling and unnatural conflict. We have three reasons for this, and we will state them in the order in which they are most likely to strike their minds.

1st. We do not believe that this war is waged for the purposes of freedom.

2d. If we did believe that those who are fighting are sincerely and earnestly bent on promoting freedom as their object, we do not believe they can attain that object by fighting.

3d. Even if we thought they could attain it by fighting, we could not, without an utter abandonment of our principles, give them our sanction and approval.

1st. We do not believe that this war is waged for freedom. It is not waged for freedom, but for Union and empire. Surely, those who are authoritatively directing the whole policy of the war must be held to be the most competent witness as to their own purpose and design. It is impossible to conceive of anything more explicit on this point than their testimony. Here is the language of President Lincoln:—“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and it is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it; and if I could do it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it; and if I could do it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that. What I do about slavery and the colored race, I do because it helps to save this Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help the Union.”

But, the, we are told there is the President’s Proclamation. True, there is the President’s Proclamation; but does that imply that the object of the war is the freedom of the slave? Why, it implies precisely the reverse. It implies that the freedom of the slave is to be used, or not used, as it may be found conducive or otherwise to a totally different object. “The principle at stake is entirely disregarded, and emancipation promised as a mere incident in the war. The Government liberate the enemy’s slaves as it would the enemy’s cattle, simply to weaken them in the coming conflict. The promise is not even unconditional,—nay, it is not made conditional on any act or omission of the black race. The act professes to be done for their benefit; but if their masters return to the Union before the 1st of January, then the slaves are to continue on in their condition of slavery as long as such masters shall choose. The principle asserted is, not that a human being cannot justly own another, but that he cannot own him unless he is loyal to the United States. We picture to ourselves the Federal Government, like a huge giant, who snatches the slave from the grasp of the South, and then takes hold of him be the feet, and wings him round and round as one brandishes a bludgeon, in a threatening attitude round one’s head, ready, whenever it is found necessary or expedient, to hurl him like a missile from a catapult in the face of the enemy, utterly heedless whether the unfortunate negro is crushed by the impact, provided only he does some damage to the foe. And does this import any great love for the negro? Why should any of us, in this country, persist in practicing an elaborate imposition upon ourselves, by trying to believe that the North is fighting for the abolition of slavery, against the explicit and emphatic declarations of the men themselves? Surely, if there is a man on the whole Western Continent whose testimony must be deemed conclusive on this point, it is Mr. Charles Sumner. What does he say in the great speech he lately delivered at Boston? Here are his own words:—“And, now what is the object of the war? This question is often asked, and the answer is not always candid. It is sometimes said that it is to abolish slavery. Here is a mistake or a misrepresentation. It is sometimes said, in flash language, that the object is ‘the Constitution as it is,’ and ‘the Union as it was.’ Here is another mistake or misrepresentation….Not for any of these things is this war waged. Not to abolish slavery, or to establish slavery; but to put down the rebellion.” We say, then, the war is not for freedom, but for Union and empire. We do not say, observe, that this may not be a very important object. We at any rate in this country, who are eternally boasting of a dominion on which the sun never sets, and who are not willing to surrender to justice or liberty the smallest fragment of our huge possessions, however acquired, have no right to speak opprobriously of such an object. but we have a right to keep distinctly before our minds that that is the object, and refuse to be cheated of our sympathies under false pretenses.

2d. But we observe, secondly, that even if the war were sincerely waged for freedom, we do not believe that the object can be attained by fighting. In the language of Mr. Gladstone—not in his recent speech at Newcastle, but in one he delivered many months ago, and containing as we thought then, and think still, the wisest word spoken in this country on the American question,—“We have no faith in the propagation of free institutions at the point of the sword. It is not be such that the ends of freedom are to be gained. Freedom must be freely accepted and freely embraced . You cannot invade a nation in order to convert its institutions from bad ones into good ones; and our friends in the North have, as we think, made a great mistake in supposing that they can bend all the horrors of this war to philanthropic ends.” Yes, we fully concur with Mr. Gladstone, that they have made, and are making, an enormous mistake. Lust, hate, violence and carnage, are not the fitting foster-mothers for freedom, and least of all for a freedom professing to be founded on the benevolent brotherhood of the gospel. To our thinking, the deliverance of four millions of oppressed and degraded human beings from the bondage of generations, and their safe introduction to the possession and enjoyment of liberty, is a task requiring a rare combination of the statement’s wisdom and the Christian’s patient philanthropy. But our American brethren think this transition can be effected by what they vauntingly call “the war power”—a power which represents only the mere rampant ascendancy of brute force, and acknowledges no allegiance to law or conscience or Christianity. We have no faith in the war power, as the minister of justice and mercy. Even if it succeeds in breaking the bonds of slavery, we see no prospect for the miserable negro, on which we can dwell with any complacency. Tempted to forsake his home in the South after, perhaps, having helped to blast it with fire, and to drench it in blood, what is to become of him? The free States of the Wet are passing laws in hot haste forbidding him to put his foot within their territory. The millions of Irishmen that people the North, aided abundantly by the intense prejudice of the Northerners themselves, loudly protest that he shall not come there to lower the rate of wages, and, as they conceive it, to degrade the character of labor. Poor Mr. Lincoln, at his wits’ end, proposes to ship him off to Central America, and so be rid of the nuisance. The authorities in Central America hurl back the proposal with indignation and contempt. If anybody can find much comfort in this prospect, as regards the four millions of American slaves, we confess we cannot.

3d. But, finally, even if it were certain that freedom would come out of this war, we could not, without an utter dereliction of our principles, give it aid or succor in any way. Our principles are that we have not liberty to do evil that good may come; that the end does not sanctify the means; that we may not destroy or punish one crime by the commission of another, at least as great, if not greater. If we are asked what is the evil which this war is doing, we answer, Circumspice. Some anti-slavery men can see only one evil in God’s universe. Provided that is pursued and assailed, they are willing to wink at every other wickedness, however atrocious, at every other calamity, however appalling. But there are men, whose sympathies for freedom are as large and generous as their own, who cannot thus shut their eyes to facts. And when we look around at the state of things which now prevails in American as the result of this war, what do we see? We see the whole land filled with violence and blood, and with all the hideous immoralities—corruption and fraud, drunkenness and licentiousness—which ever accompany war. We see men’s minds becoming more and more envenomed with the blackest malignity towards each other. We see the voice of Christianity openly set at nought (Sic) by thirty millions of professing Christians, and the very ministers of religion, whenever the authority of Christ as the teacher of love and peace may seem to impose any restraint on the indulgence of the most violent of human passions, saying by the whole tenor of their teaching, “Let us break his bonds asunder, and cast away his cords from us!” We see in the distance the coming of yet greater woes; for every day the war is prolonged the evils we have enumerated will become more aggravated, the carnage more desperate, the ferocity more fiendish, the practical abnegation of Christianity more audacious and defiant. And if the will of the North can be only seconded by its ability, we see the war becoming a war of utter extermination against the South. “Sooner than see this Union severed,” says one of their so-called statemen, “let not only the institution of slavery perish, but let the habitations that have known it perish with, and be known no more forever.” “It is better,” says one of their so-called ministers of the gospel, “far better, that every man, woman and child, in every rebel State, should perish in one widespread, bloody and indiscriminate slaughter; better that the land should be a Sahara; be as when God destroyed the Canaanites, or overthrew Sodom and Gomorrah, than that this rebellion should be successful.”

Let our readers observe that the object with all these people is not the abolition of slavery, but the conquest of the South. But if their object were the abolition of slavery, we say we cannot lend our sanction to do all this evil that good may come, even if there were the slightest probability of its ever coming by such infernal means. We must say, candidly, we are not prepared to buy the freedom of the slaves at so tremendous a cost.—London (Eng.) Herald of Peace.

“The War in America,” The Liberator (Boston, MA), November 28, 1862, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84031524/1862-11-28/ed-1/seq-4/.