The foundational principles and civic virtues that form the bedrock of the American system of government were deliberately designed for a moral and religious people, as John Adams famously declared: “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”1 This assertion underscores the profound truth that our republican form of government is not a self-sustaining mechanism but a delicate framework that depends on the character and responsibility of its citizens. The system was crafted to foster self-governing, self-sufficient individuals—citizens capable of exercising moral agency in both their personal conduct and their interactions within society. Far from being a utopian fantasy or a dystopian imposition, this system is grounded in the realistic expectation that a free society thrives only when its people cultivate individual virtue and take responsibility for their actions. It is a government meant for mature, responsible adults who engage in a voluntary market characterized by both competition and cooperation, promoting liberty rather than enslaving its citizens to centralized control or dependency.

The philosophical foundation of this system rests on Natural Law and Christian principles, which together establish a framework for what has been referred to as the “Law of Liberty.” This concept, rooted in both ancient and biblical traditions, emphasizes the inherent dignity of the individual and the necessity of personal accountability. Natural Law, as articulated by thinkers like John Locke and reflected in the Declaration of Independence, holds that individuals are endowed with inalienable rights by their Creator—life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. These rights are not granted by government but are inherent to human nature, and the role of government is to protect, not infringe upon, these God-given liberties. Similarly, Christian principles, particularly those drawn from the Judeo-Christian ethic, emphasize virtues such as justice, charity, and personal responsibility, which are essential for maintaining a free society. The ancient Law of Liberty, as referenced in the Epistle of James, speaks to the moral freedom to choose righteousness—a freedom that requires discipline and integrity, not coercion or compulsion.2

Consider the immense challenge and responsibility required to sustain such a system. A government designed for self-governing individuals demands a citizenry capable of balancing personal liberty with civic duty. It is not a system that promises perfection or the eradication of evil, for no earthly government can eliminate human imperfection or sin. The existence of opposition in all things—a principle affirmed in both religious texts and the observable realities of human nature—ensures that moral struggles will persist. The presence of sin or wrongdoing is an inevitable part of human existence, and no government, no matter how well-designed, can “destroy” evil without destroying the very freedom that allows individuals to choose virtue. The American system, therefore, is not about preventing all sin or shielding citizens from the consequences of their choices; rather, it is about creating the conditions under which individuals can freely choose to act virtuously, thereby developing their character and contributing to the common good.

This emphasis on moral agency stands in stark contrast to systems that rely on force or coercion to achieve compliance. Coercion is itself an evil, antithetical to the virtues of persuasion, reason, and voluntary cooperation. The American republic was not established to compel citizens to act rightly but to provide a framework in which they are free to make moral choices. When government is used to enforce virtue or control behavior beyond the protection of individual rights, it undermines the very liberty it is meant to preserve. History provides ample evidence of this danger: regimes that seek to impose moral conformity through force—whether through authoritarian laws, excessive regulation, or punitive taxation—inevitably erode personal responsibility and foster resentment rather than righteousness. As philosopher Edmund Burke warned, “Society cannot exist unless a controlling power upon will and appetite be placed somewhere, and the less of it there is within, the more there must be without.”3 The American system assumes that this “controlling power” resides primarily within the individual, not in the heavy hand of the state.

Yet there is a troubling tendency among those who struggle to govern themselves to turn to government as a tool for controlling others. This misuse of governmental power often manifests in policies that encroach upon individual liberties, confiscate private property through excessive taxation, or redistribute the fruits of others’ labor to enforce a particular vision of “justice.” Such actions violate the foundational republican principle of limited government and represent a form of theft, cloaked in the guise of public good. The virtuous path, by contrast, is one of persuasion, mutual respect, and voluntary cooperation. It requires individuals to take responsibility for their own behavior rather than seeking to impose their will on others through the coercive apparatus of the state. The American Founders understood this, designing a system that decentralizes power and encourages citizens to cultivate the virtues necessary for self-governance—virtues such as diligence, integrity, and charity.

This misuse of government often stems from a failure to recognize the universal principle of opposition in all things. The existence of competing interests, ideas, and moral choices is not a flaw to be eradicated but a reality to be embraced. A free society must tolerate differences and disagreements, provided they do not infringe upon the rights of others. Attempts to eliminate this opposition through government intervention—whether by silencing dissent, enforcing conformity, or redistributing resources to suppress inequality—distort the delicate balance of liberty and responsibility. As Thomas Jefferson observed, “The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others.”4 When government oversteps this boundary, it ceases to be a protector of liberty and becomes an instrument of oppression, undermining the very principles upon which the American republic was founded.

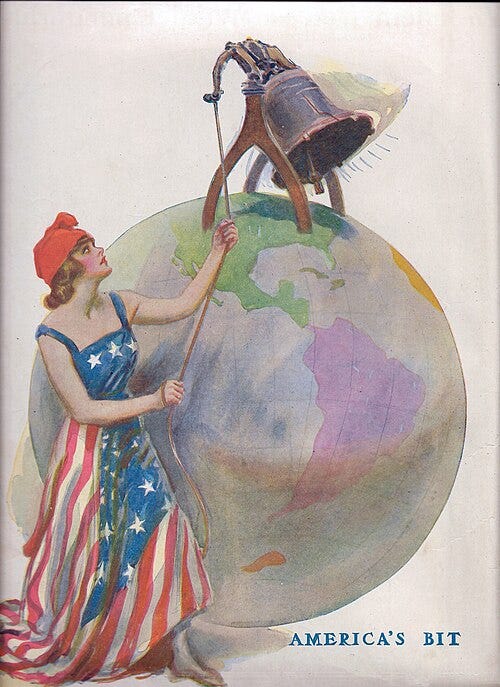

In conclusion, the American system of government, rooted in Natural Law and Christian principles, is a testament to the belief that liberty and virtue are inseparable. It is a system designed not for the faint of heart or the morally indifferent but for a people willing to embrace the challenge of self-governance. It rejects the false promise of utopian perfection and the tyrannical impulse to eradicate evil through force. Instead, it calls upon citizens to exercise their moral agency, to choose virtue over vice, and to engage in a voluntary society that balances competition with cooperation. The preservation of this system requires vigilance, not only against external threats but also against the internal temptation to use government as a tool for coercion rather than a guardian of liberty. By recommitting to the foundational principles of individual responsibility, limited government, and moral agency, Americans can ensure that their republic remains a beacon of freedom for generations to come.

The American republic, built on the principles of liberty, virtue, and self-governance, calls us to a higher standard of personal responsibility and moral agency. To delve deeper into the tensions between individual freedom and state overreach, I invite you to explore two related articles I’ve written. In “Unmasking the State: How Coerced Charity Devours Liberty and Souls,” I examine how state-enforced welfare undermines the moral and spiritual rewards of voluntary charity, eroding both liberty and human dignity. Similarly, in “Muh Rights!”, I unpack the true nature of natural, inalienable rights and distinguish them from the often-misunderstood concepts of positive rights and civil liberties, clarifying how government’s role is to protect, not grant, our inherent freedoms. Both pieces expand on the ideas of limited government and personal accountability central to this essay, offering further insight into preserving the delicate balance of a free society. Check them out to continue this vital conversation about liberty and responsibility.

“From John Adams to Massachusetts Militia, 11 October 1798,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-3102.

James 1:25 (King James Version).

Edmund Burke, Maxims and Opinions: Moral, Political, and Economical, with Characters, From the Works of The Right Hon. Edmund Burke, Vol. 1, (London: C. Whittingham, 1804), 176.

Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, 2nd ed., (Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1794), 231.